Dir: Hideaki Anno

Dir: Hideaki Anno

2004

Eriko Sato started off her life as cute bikini model in Japan, but has now jumped to film by grabbing the lead role in “Cutie Honey,” a purple and pink psychedelic blast of live-action anime based on the ’70s manga by Go Nagai. As her theme tune tells us, she has “perfect boobs”, kitten-like lips, a fine behind, and generally just lives up to her name. She’s also perched somewhere between human and post-human, being as she is a recreation of her scientist father’s dead daughter, a reanimation. This also makes her a perfect heroine as well as sex object: innocent but sexual, loving but unobtainable. The film rightfully indulges in its star’s good looks and body, giving us more cheesecake than a California factory. Compare this to the huffing and puffin over nuthin’ that was “Catwoman”–Cutie Honey’s post-feminism is more honest than the bait and switch of American attempts.

Even after the CG explosion of “Kung Fu Hustle”, this film’s low-rent effects are still bracing and inventive, though after a head-spinning opening sequence, the film settles down for character building and humor before building up to a series of climactic battles between members of the Panther Claw gang and the asexual immortal called Sister Jill. The film is slow in places like many Takashi Miike films. However, we wouldn’t want to cut out such moments as a drunken karaoke evening between the three leads, including Jun Murakami as a be-capped journalist with groovy flared hair, and the button-down (but very very hot) police officer Aki (Mikako Ichikawa). Or a very silly moment when Black Claw sings a song all about himself, backed up by violin-playing henchmen.

This was the third film I’ve seen at the festival, and I was glad to see the crowd ate it up. The festival staffers all loved it as well, introducing the screening with a group call out of Cutie’s power-up magic words: “Honey! FLASH!”

Category: Film

Kung Fu Hustle

Dir: Stephen Chow

Dir: Stephen Chow

2004

I just missed Kung Fu Hustle when I was in Taiwan last November–it was set to open two weeks after I left, but what a pleasure to see that it was in the line-up at the Santa Barbara Film Festival. Apparently, S.B. marked the second American screening outside of Sundance (not counting those who have found a bootleg copy in Chinatown). Director, star, and comic genius Stephen Chow has been working on this since 2002, which is a long time compared to his productive height in the early ’90s, where they would knock off four Chow vehicles a year (and nearly all good).

“Kung Fu Hustle” makes Chow’s previous film “Shaolin Soccer” feel like a transitional piece. There was plenty of CG in that film, but now we see that Chow was working towards realizing a sort of human cartoon, where live action meets Tex Avery. Of course, The Mask also attempted this, but the boundaries between the Avery-like Mask character and the “real” world were set. The world of “Kung Fu Hustle” is completely different.

What fans of Chow might have a problem with is the lack of him for great chunks of the picture–his character appears off and on in the first half. He plays a useless street “tough” trying to get into the infamous Ax Gang, while the gang itself tries to put the heat on a innocent looking neigborhood/tenement which is secretly home to a group of kung fu masters. The centerpiece here is the landlord/landlady couple who run the tenement: the landlady (Yuen Qiu) has superspeed and the “Lion’s Roar” and the husband (once Chow regular Wah Yuen, who hasn’t been in one of his films since “Fists of Fury II”) who knows a very bendy style of kung fu. Apart from Wah and Chi Chung Lam (the fat guy from Shaolin Soccer), there’s very few familiar faces, and a great many are first time actors, a method Chow employed in his previous film.

Chow’s character makes a transition from being a wannabe gangster with blocked chi to a superhuman good-guy with chi a’plenty, and this comes later in the proceedings. The feeling is somewhat like when a stand-up comedian goes from his regular job to be an announcer for other, younger comedians under his mantle.

Is the film good, though? Oh yes, very much, with plenty of eye candy, deft camerawork (Chow knows how to shoot a fight scene), and effects that don’t drown out the rest of the film, making sure to keep the human element centered. Is the film one of his bests? No way, for there’s very little of him. But is this film unlike anything Chow has ever made, and is this film unlike anything most audiences have ever seen? Undoubtedly.

24: Season Three

Prods: Joel Surnow and Robert Cochran

Prods: Joel Surnow and Robert Cochran

2004

Season Three of 24 finally got into our greedy little hands this month, and it wasn’t long till we had blasted through the series, sitting through at least two five-episodes-in-a-row viewings. Unfortunately this season pales in comparison to the first two for a couple of reasons.

One is that, under pressure from Fox execs, I believe, to make the show accessible to any damn person who may join the show at any point during its run, the script and its structure got dumbed down a lot. Agents told other agents things they already knew, stating and restating the obvious for the benefit of nobody else except the chance viewer.

Second is that the faithfulness to the 24-hour, real-time narrative has been eschewed for a plotting structure that feels like regular TV. Yes, these events still happen in an hour during each episode, but now things happen way too fast. Despite being located near downtown L.A., nobody seems to take any time to drive to locations, with most trips taking ten minutes at most. Hell, it takes 2 minutes just to get to the car from CTU, I bet. Whoever is working the Powerpoint at CTU should get a medal, as well, because 10 minutes after data is requested, there’s a brilliant presentation full of animated graphics and multiple click-throughs to be screened for the agents. 24 has never been the most realistic of shows, but so much of the suspense from Seasons One and Two came from the time it took to just achieve simple tasks. When time was broken down to the minute, suddenly every minute counted, and we counted along with the show. Now the show feels like a 72-hour bad dream.

The show continues its balance between one of the most moral administrations in the history of fictional presidencies, and between the ruthless, cold agent assigned to protect it. Jack Bauer never speaks of his country or of the freedoms he (or others) enjoy here and that he’s protecting. He’s there to protect the President and by proxy the American people (usually presented as a mob of extras, as all other characters are agents, villains, or victims). Jack’s victory over emotion (which cost him his wife in the first season) is now contrasted with the “weak” agent Tony, who acts selflessly when his wife is threatened and is punished for it by show’s end. Like George Romero’s zombie films, 24 punishes those who acts out of emotion and a sense of family, and rewards those who don’t. That may include the villain, but his undoing is when Jack threatens the life of his daughter.

Like Season Two, this season presents torture as a common practice for both sides. In a year that has brought us Abu Ghraib and torture’s legal architect Alberto Gonzales, these scenes disturb, though set up as being as a desperate last option. And torture in 24 always leads to vital information, unlike in real life.

The structure of the season began to show more this time ’round. There’s a “beta criminal” that takes up the first half of the season, whose death or capture leads to the surprise revelation of “alpha criminal” whose death or capture caps the penultimate episode, with loose ends tied up in the final episode. There will also be a sacrifice among the CTU staff. And emotional women will wind up ruining everything as usual. (Exception: Reiko Aylesworth’s Michelle, who plays by the book, leaving husband Tony as the emasculated male).

So, for now, we’re sticking with the series, though we were disappointed. In a year we’ll have Season Four to contemplate, and see if the show got back on track.

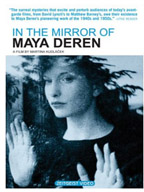

In the Mirror of Maya Deren

Dir: Martina Kudlacek

Dir: Martina Kudlacek

2003

A gift from my buddy William (along with a Brakhage documentary I haven’t watched yet). For those of us who know Maya Deren from her short body of work (but what films they are!) and some of her writings, this documentary allows us a glimpse into the world of the first major woman filmmaker and one of the most important experimental directors of the 20th century. She was a proto-hippy, a proto-feminist with her wild hair, Spanish dresses, and deep interest in other cultures (mainly Haiti). According to Brakhage, who is interviewed here and talks in a most wonderful voice, Deren got so involved in Haitain Voudou that she could call the spirits, and even cursed Brakhage with ill health when he was late to a show. And I believe it too.

For me, I would have liked a bit more on “Meshes of the Afternoon,” which inspires me everytime I watch it. I’ve heard it was shot either up around Mulholland Drive or Laurel Canyon. That long, long curving road speaks to me of a dream from childhood–familiar yet strange. Surely somebody knows that address.

Despite being a visionary and responsible for getting experimental film shown in the States, she died young (45, I believe) and poor, unable to scrape together the cash to finish the movies she was planning and working on. We get some tittilating shots of rolls and rolls of film sitting in her film archives, but very little of the footage itself. She burned brightly and fiercely and then was gone. Damn.

Another case for Creative Commons

In what is sure to be one of today’s most-blogged stories, this Globe and Mail article on how copyright is killing documentaries makes the case for new, more flexible ways of thinking about copyright–and how greed trumps information and education. Well, duh, you commie.

As Americans commemorate Martin Luther King Jr. and his legacy today, no television channel will be broadcasting the documentary series Eyes on the Prize. Produced in the 1980s and widely considered the most important encapsulation of the American civil-rights movement on video, the documentary series can no longer be broadcast or sold anywhere.

Why?

The makers of the series no longer have permission for the archival footage they previously used of such key events as the historic protest marches or the confrontations with Southern police. Given Eyes on the Prize’s tight budget, typical of any documentary, its filmmakers could barely afford the minimum five-year rights for use of the clips. That permission has long since expired, and the $250,000 to $500,000 needed to clear the numerous copyrights involved is proving too expensive.

The Wire: Season One

Prod. David Simon

Prod. David Simon

2002

Recommended by Jon, and in the back of my mind since reading a laudatory article in Salon about it, the first season of Wire was my first order on Netflix. (Yes, we’ve signed up). David Simon’s story of a Baltimore drug kingpin and the team assigned to bring him down takes delight in upending every cop show cliche, and not just for effect’s sake, but because that’s the way the world works, baby. So instead of brilliant cops going rogue after being told they’re off the case by their cigar-chewing boss, we have cops and detectives brought down by bureaucracy and their own weaknesses. There’s no dialog-for-dummies here, either; characters reference events several episodes previous and we’re just expected to know. On top of that put the dueling patois of the drug dealers (garden variety Ebonics laced with phone-is-tapped shorthand slang) and the cops (cynical, pseudo-racism mixed with procedural jargon) and you’ve really got to prick up your ears. Characters reveal themselves slowly–our “hero” McNulty comes across later as rather selfish; rising dealer Dee is a street thug trying to figure out a right way to live in a society that’s all wrong. There’s none of the safe humor of The Sopranos here, nor a need to ratchet up the suspense. What we get instead is a chance to explore the minutia of the typical drug enforcement case. Salon calls it “novelistic”–in its breadth I’d have to agree. The ending of Season One puts the show on the level of political films as “Z,” a world where no good deed goes unpunished.

Nightwatch

Dir: Ole Bornedal

Dir: Ole Bornedal

1997

Ewan McGregor plays a law student who gets a job as a night watchman in a very spooky medical center, where one of his nightly duties is to walk across the stiff-filled morgue and turn a key. If this building had been inspected by any state-run agency, it would have been shut down: faulty lighting, crummy-looking halls, and an open sewer nearby. Instead, this is a perfect place for a thriller. The best part of this remake of a 1994 Dutch film is the setup, where we are given a tour of the medical center and introduced to several upcoming plot points and red herrings. There’s even an alarm just in case a corpse revives and needs to call for assistance. Being left alone in a big spooky place with nothing but your mind to play tricks on you guarantees some jolts, but this is a thriller, and–just as in the original–there’s a serial killer out there, a number of bodies, and a young nightwatchman to frame for the murder.

There’s far too much music in this film, especially when silence would have done the job, and alert viewers will guess the killer in the opening scenes. All that remains is an effective scene with a prostitute in a restaurant, Nick Nolte’s weary cop (Nolte and weary like each other so much they should get married), and an early glimpse of John C. Reilly in a supporting role.

Light Sleeper

Dir: Paul Schrader

Dir: Paul Schrader

1991

Paul Schrader’s film of a drug dealer trying to get on with life though he knows it’s probably passed him by, is a lighter, NewAgey-er version of his Taxi Driver, with William Defoe keeping a diary and surveying the garbage that lies in his path, metaphorically and literally (there’s an interminable garbage strike that threatens to swallow New York throughout. Susan Sarandon plays his supplier, who also plans to get out and go legit with a makeup company. Pushing him to find a way out is the random appearance of his ex-wife (Dana Delaney) who knows she shouldn’t get involved again. This is a city of expensive apartments and restaurants, where even a ratty apartment looks nicer than anything in Taxi Driver. But, like that film, Light Sleeper will end in blood, something to wash away the streets.

It’s a very sad, hopeless movie, though the characters are more in-control and nobler. It still doesn’t help them out of the hole they’ve dug for themselves.

The film is marred by a lack of momentum and a bloody awful song that plays throughout, which sound like Leonard Cohen crossed with Michael Bolton. It truly was cold-turkey music.

Irma Vep

Dir: Olivier Assayas

Dir: Olivier Assayas

1996

I had forgotten how much of this film’s ending I had ripped off for my film, so much that when it came I sat slightly embarrassed next to my wife, who just said, “hey, it’s Nowhereland!”

But it’s to the credit of Assayas’ film that all it took was one viewing and I immediately absorbed the ideas and lessons that the last 3 minutes teach.

That said, the film is both a love letter to Maggie Cheung (in a rubber suit! looking gorgeous!) and French film. For most of the film is about the latter and the problems of advancing the state of film from those who either want to pronounce it dead and nothing like America (the dumb journalist who interviews Cheung) or the others who want it to rehash what has come before (the remake of Les Vampires that forms the movie within the movie). Various positions are staked out, nothing gets consummated–from art to sex, life flows on continuous, and what is left is the most personal kind of film of all, an oblique experimental art piece inside a film that mixes the avant-garde with realism. All that and Luna covering “Bonnie and Clyde.” I love it.

Double Vision

Dir: Kuo-fu Chen

Dir: Kuo-fu Chen

2002

Double Vision transplants a Seven-like serial killer tale into Taiwan and a strange Daoist cult. Victims believe themselves to be drowning or burning alive, and die appropriately. Could it be “pure evil” or some strange sort of science? Enter an American expert on serial killers (David Morse) and a workaholic cop (Tony Leung–the other one) who has been ostracized for exposing corruption. The buddy cop dynamics are out of an X-Files episode, as is the set-up, but Double Vision transcends its rather cliched beginnings and veers off into something dark and menacing. The truth here lies somewhere between science and religion, and both men are right in their own way while being wrong in more important ways (ie. those that would save lives).

I liked it more than I thought I would–a great pall of evil and corruption hung over the entire film, permeating even the police office where, supposedly, equilibrium can be found. There’s even a bloody massacre of cops’n’cultists in the third act that I never expected, but which have done Peckinpah proud. Morse, who is best known for being in nearly every Stephen King tele-movie, but who I know as the cop that Bjork kills in “Dancer in the Dark,” keeps his dignity throughout in a project that so desperately wants to compete with the West. But it succeeds on what makes it particularly Taiwanese: the Daoist angle, the audience’s knowledge of Daoist visions of hell, and a lack of Hollywood structure near the end. Even in its sillier moments, it takes itself seriously, and manages to be chilling.